The MaRIUS project has hosted three international Symposia to bring together practitioners working on aspects of drought and water scarcity from across the world. These Symposia have been public focused, and open to everyone.

The events have been very successful, attracting a large audience each year, and have helped disseminate work on drought and water scarcity across many different related topics by academic researchers, governmental regulators, and companies, to a wide audience.

-

The first MaRIUS inspired Drought Symposium, Drought Risk in the Context of change, was held on Monday 22nd September 2014 at Magdalen College, Oxford.

-

The second Drought Symposium, Drought Risk and Decision Making, was held on Tuesday 8th September 2015 at Exeter College, Oxford.

-

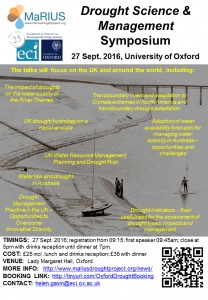

The third Drought Symposium, Drought Science and Management, was held on Tuesday 27th September 2016 at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

Below is a summary of each of the three events, with links to the presentations and podcasts where available.

Drought Science and Management

Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. 27 September 2016

The MaRIUS project is proud to have held the last of its trio of International Symposia. The Symposium, “Drought Science and Management” took place on 27 September 2016, at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

This Symposium focused on Drought Science and Management in the UK and around the world, and had a mix of oral & poster presentations.

Speakers & titles

- Doug Hunt, Atkins: Water Resource Management in the UK

- Ian Pemberton, Ofwat: “Moving to a national approach to water management”

- Mike Morecroft, Natural England: “Effects of drought on UK ecosystems and the implications for nature conservation in a changing climate”

- Gianba Bussi, University of Oxford: “The impact of droughts on the water quality of the River Thames”

- Sarah Whatmore and Catharina Landstrom, University of Oxford: “Co-producing knowledge for local drought resilience”

- Gemma Coxon, University of Bristol: “Drought hydrology on a national scale”

- Kevin Grecksch, University of Oxford: “Drought Management Practice in the UK – Opportunities to Overcome Innovative Scarcity”

- Dustin Garrick, University of Oxford: “Transboundary Rivers and Adaptation to Climate Extremes (TRACE): Learning from Severe Droughts”

- Henny van Lanen, Wageningen University, Netherlands: “Drought indicators – their usefulness for the assessment of drought types, impacts and management”

- Lee Godden, University of Melbourne, Australia: “Water law and drought in Australia”

Drought Risk and Decision Making

Exeter College, Oxford. 8 September 2015

Droughts threaten societies, economies and ecosystems worldwide, and can lead to potential losses of £billions. Yet our ability to characterise and predict the occurrence, duration and intensity of droughts, as well as minimise their impacts, is often inadequate.This symposium brought together global experts on the processes that cause drought and their consequences. It will take an interdisciplinary approach, looking at the climatic and socio-economic factors that are contributing to the changing risk of drought. The symposium forms part of the NERC UK Droughts & Water Scarcity Programme.

There were three themes covered by a mix of oral and poster presentations

- UK Drought Science and Policy

- Understanding the social dimensions of drought

- Drought Science and Policy from around the world

A written summary of the oral presentations given at the Symposium is available below. There are also podcasts from the event, as well as others, available here.

Summary of Oral Presentations

By Alice Chautard, with inputs from Franziska Gaupp, and Helen Gavin.Jim Hall, University of Oxford: Introduction

- Looking at drought from a combination of perspectives (and in fact a highly interdisciplinary combination of funders supporting the project).

- Aims to develop the thinking, methodology and framework to inform risk-based decision making i.e. making use of some explicit analysis of impacts form a range of different perspectives (economic, social, environmental).

- To some extent risk-based decision-making is happening already (e.g. 2009 Water Resource Plan) BUT there is still some disconnection between water resource planning and drought planning. Besides, the process is overall utility focused with limited quantification of the scale of different impacts.

- Thanks to funders.

Helen Gavin, University of Oxford: Introduction to UK Droughts & Water Scarcity Programme

Presentation of UK Droughts & Water Scarcity Programme, and the four projects it has funded:

- WP1: Analysis of Historical Drought (in a nutshell: aiming to understand past drought, and how we reacted to them, to be better prepared for future droughts and thus shape our policies). Led by Jamie Hannaford at CEH

- WP2: Forecasting Drought (in a nutshell: improve forecasting of drought). Led by Len Shaffrey at University of Reading

- WP3: Impacts of Droughts – 2 projects. DRY: looking at social and physical science elements, led by Lindsey McEwan at UWE. And the MaRIUS Project, led by Jim Hall at the University of Oxford.

Christina Cook, University of Oxford: Regulatory governance arrangements for water scarcity and drought in the UK

Play video View slides- Research focuses on: understanding how drought and water scarcity are regulated in the UK: how the law works in practice; regulatory tools as part of a wider governance space; How can are environmental science and economic knowledge used and can they be better connected;

- She reviews the different actors involved in the governance space, and the relationships they have with one another. She then reviews some of the main tools used for governing and regulating water services, and presents some of the findings of her research

- Notes on the governance space

- The department for environment, food and rural affairs is the lead government ministry;

- On the regulatory side: environment regulator, water quality regulator; economic regulator;

- The Environmental Agency;

- Water and Supply providers;

- consultants

- Mapping the governance space – how:

- Looking at droughts planning; EA Abstraction reforms; historical experience of drought permits and orders (2003-06; 2010-12 droughts).

- Methods: Academic literature, government policy, company documents, regulatory analysis (law and regulation), empirical work (interviews: water company, water regulators, companies, farmers etc.)

- Main pieces of legislation: Water Industry Act 1991 (what companies need to do):

- Mapping drought planning in England (relations between different actors)

- Black box: much of the planning is subject to administrative law review.

- EU: no specific water scarcity and drought directive, but WFD, SEA and HRA

- Defra has legislation: Water Industry Act, policies based on white paper that frame drought planning

- EA: provide a guidance document that water companies can use when drafting drought plans;

- Drought Management Options:

- Demand type measures (incl. hose pipe bans) vs. supply type measures (incl. drought orders and permits). Main findings:

- Temporary use bans – findings: companies apply them in many different ways and for different reasons (only for domestic use; each company uses different ‘formula’ different combination of measures;

- Drought permits (companies apply for DP from EA):

- Drought orders can restrict use or impact abstractions and discharge (ordinary or emergency DO);

- Demand type measures (incl. hose pipe bans) vs. supply type measures (incl. drought orders and permits). Main findings:

Context is key; one size does not fit all; past experience of drought is very important in how companies develop their drought plans;

- Role of Consultants is key: they have major relations with the EA, Ofwat, water companies and virtually every actor of the governance space; bring invaluable expertise;

- Other finding: variability in relationship between EA and water companies (places where this is working well, and others where it isn’t necessarily so).

- How environmental science and economic knowledge are used – e.g. strategic environmental assessment: how are companies are understanding the value of these tools, when do they use them or not. Work in progress.

Benoit Guillod, University of Oxford; Western US drought attribution, and the generation of synthetic multi-year UK drought events for risk-based impact studies

Play video View slides- Meteorological hazards

- Two projects:

- Western US Drought: Whether climate change played a role in drought generation

- MaRIUS : generation of synthetic multi-year UK drought events for risk-based impact studies

- By definition extreme events are rare, so very difficult to quantify probability; In general look at the probability or the frequency of an event, and how that has changed over time (how that correlates with climate change).

- Use Weather@Home — simulate a lot of different weather events

- US Drought Project:

- Potential reasons for the drought:

- Western US climate affected by ENSO; when the drought started it corresponded with La Nina conditions, so it was thought drought was caused by La Nina; however we are now entering into El Nino condition and the drought is continuing.

- ‘The Blop’ – anomaly of sea surface temperature in winter 2013-14 (very warm anomaly in north eastern Pacific >2 degrees Celsius)

- Climate Change?

- Run simulations to test hypotheses using Weather@home (18 months run: 12/2013-05/2015) in order to test what is to blame for the US drought: climate change, the ‘blop’ or natural climate variability. Analysis ongoing.

- Potential reasons for the drought:

- MaRIUS: Using Weather@home to produce a synthetic set of droughts and heat waves. weather@home is a public science initiative whereby people can run climate models on their private computers (see: climateprediction.net)

- Creating two drought datasets:

- A hind cast of past droughts (goes back to 1850)

- Synthetic event set of present and future hydrometeorological droughts in UK

- Creating two drought datasets:

Lola Rey, University of Cranfield: Evidence of increasing resilience in the irrigated agricultural sector in the face of increasing water scarcity

- Research Question: Are there any evidence to suggest that farmers are more resilient to drought and water scarcity?

- Usually farmers are the first affected by drought; In the UK irrigated is highly productive (total 250M pounds from irrigated agriculture in a dry year).

- Past UK droughts: 1976 is remembered as one of the most severe droughts, but looking back in time, there have been many other. Have farmers become more resilient?

- Case Study in the Anglian region: where most of irrigated agriculture is concentrated; EA manages the abstraction through statutory licensing system.

- Methodology:

- Farmers Interviews: risk perception; impacts of past droughts; response/management; areas for improvements; climate change

- Drought Managers: management actions; drought abstraction

- Results:

- Many different ways of looking at drought;

- Most farmers see drought as a very important risk for the business (73% believe droughts will be a great problem in the future);

- The way farmers respond to drought has changed: In the last drought farmers agreed to take some voluntary restrictions in order to avoid mandatory restrictions – working together.

- 2010-12: more positive about how farmers have managed droughts: received better forecasting, better information.

- Coping vs. adapting:

- Short term adaptation (coping): change in irrigation patterns etc.; most important factor when responding to drought is the type of crops grown; sensitivity of the crops.

- Long term actions: investment in alternative water sources (e.g. on farm reservoirs).

- Farmers see the EA as being more proactive (EA meeting with farmers, more engaged, provide more information)

- Area for improvement: farming sector should have a more central role in water resource management; better forecasting; more flexibility in the way the water is allocated/used (e.g. use of water trading)

- Conclusion: farmers are adapting in the Anglian region, and seem to have a more positive attitude about the role of the EA. Increasingly collective action (creation of water abstraction groups, which are useful for farmers during drought).

Paul Whitehead, University of Oxford: Impacts of Droughts on Water Quality

- Water Quality impacts of drought in the UK

- Key Water Quality Variables to consider: DO, nutrients: Phosphorous, nitrogen; sediments; carbon; acidification; metal; organics; ecology (fish, microphytes); In this presentation Paul reviews some of these WQ variables and how drought impacts them by looking at specific research case studies he has been involved with/ and how MaRIUS contributes to fill the gaps.

- The Upper River Kennet ecology and Dissolved Oxygen

- Decaying macrophytes at the end of the summers: affects fish/ecology; specific to low flow/eutrophication;

- Important from an ecology point of view: drop in dissolved oxygen affects river ecology, fish can die./li>

- Understand and model interactions between flows, concentrations, ecology; which is what the Water Quality dimension of MaRIUS aims to research.

- Thames Water Quality & Flow 1974-76

- As flow decrease, increase concentration in phosphorous (less dilution). Mass balance models can simulate that effect.

- Serious from a WQ point of view: moving away from the Water Framework Directive.

- Flushing-Effect: what happens post-drought (key element in MaRIUS)

- Flush of nutrients moving down the river. Can these be modelled?

- 1975-2008: Dunham WQ series: useful for exploring long term trends; form an ecology point of view research how species are changing over time.

- Model the whole of the river Thames System. Using INCA: linking what is happening on the land system (agriculture, urban etc.), and what is going on in the river. In particular model P concentrations.

- New: creating a new model for algae, applying phytoplankton model.

- Alex Elliott is modelling reservoir

- Climate Change: how is CC affecting water quality?

- Conclusion and main research questions:

- Focus on the Thames is a key part of the MaRIUS project, but MaRIUS aims to focus on the national scale

- How does water quality constrain water resources?

- How do we build knowledge into water planning models?

- How will CC affect droughts & Water quality?

Len Shaffrey, University of Reading: IMPETUS: IMproving PrEdictions of Drought To inform USer decisions

- Research aim to improve forecasting of drought in the UK; part of WP2. (Meteorological aspects + hydrological aspect)

- Seasonal forecast: meteorological conditions that cause drought in the UK:

- NAO (Q: how predictable are NAO oscillation on seasonal time-scale? A few-years ago we would not have been able to predict NAO a couple month in advance; predictions are now getting better)

- UK precipitation and rainfall: linear relationship with NAO; use the information to down-scale forecast.

- Other research question: Focus on longer time-scales: inter-annual precipitations (comparison between east and west of UK)

- From a hydrological perspective: linking land surface models with recharge models/groundwater models (BGS looking at groundwater aspects).

- IMPETUS: consideration of water demand, which is very tricky (with focus on specific areas);

- Question around up-take of drought forecasts: how should probabilistic forecasts be used to inform decision-making?

- Over-all issue of scale (geographic and time) is central: aims to improve resolution.

Emma Weitkamp, UWE: DRY – interweaving of science and narrative in decision making about drought, water scarcity and heat waves

- Bridge between science (hydrology/ecology) and

- One of the 2 projects under WP3: Develop a resource for drought risk management.

- Draw a range of perspectives from the scientific community & from other drought stakeholders (anybody with an interest in drought): explore how these different groups understand and relate to drought research and drought risk. Aim to bring together the different knowledges.

- Project looks at 7 catchments – chosen to represent different climate gradient, urban/rural.

- Use the ‘deficit’ approach: Historical belief that if we can communicate science better, the decision-making process will be better. It turns out this is not true: a lot of other factors influence decision-making. So how can we integrate these different factors/knowledges/understanding of drought? How can we bring them together to aid the decision making process?

- Different elements of the research:

- Natural science workshop which brings together scientific modellers, artists, and other science communicators.

- Collect stories about how people live drought, the human faces behind drought

- Citizen science aspect how to bring/engage citizens in the data collection/science aspects of drought (e.g. tree measurements)

- Narrative workshop at catchment level to think about how drought modelling will impact on local level.

Kevin Collins, Open University: DrIVER – Designing social learning systems for improving drought monitoring and early warning

- DRIVER Project: Improving the link between hydro-meteorological drought characterization of drought and environmental and socio-economic impacts. How relevant are drought indicators at capturing drought impacts/severity? How can we better design indicators to incorporate elements of drought impacts?

- Methodology: Combine hydro-meteorological and socio-economic data such as reports, and social learning approaches to incorporate stakeholders’ views and experiences of drought.

- Workshop around the following question/conversation: how do we know we are in drought? Pulling out a range of issues that matter for stakeholders involved:

- Issues around forecasting, impacts, resilience, governance etc.

- Issues around public health

- What kinds of drought are we in? Impacts on the economy.

- Vulnerability

- Key finding: There are many different kinds of droughts, so people experience drought in different ways

Rebecca Pearce, Stuart Barr, Exeter University: History – Constructing social timelines of droughts in the UK

- DRIVER Project: Improving the link between hydro-meteorological drought characterization of drought and environmental and socio-economic impacts. How relevant are drought indicators at capturing drought impacts/severity? How can we better design indicators to incorporate elements of drought impacts?

- Methodology: Combine hydro-meteorological and socio-economic data such as reports, and social learning approaches to incorporate stakeholders’ views and experiences of drought.

- Workshop around the following question/conversation: how do we know we are in drought? Pulling out a range of issues that matter for stakeholders involved:

- Issues around forecasting, impacts, resilience, governance etc.

- Issues around public health

- What kinds of drought are we in? Impacts on the economy.

- Vulnerability

- Key finding: There are many different kinds of droughts, so people experience drought in different ways

Catharina Landstrom & Eric Sarmiento, University of Oxford: MaRIUS – Seeing scales in drought and water scarcity management

- Focus on the narratives around scale. Spatial scale is a key element of studying and understanding drought (national scale: government agency, legislators, policies; regional scape: water resource norms, rivers, catchment; local scale: communities, individual water resource use)

- How are scales produced, how can we understand them?

- Eric Sarmiento: focus on two local case studies –

- River Kennet and river Lead: how do communities understand and experience drought.

- Methods: Semi-structured interviews (people who live along rivers, artists, environmentalists, river keepers etc.) and archival work.

- What happens at local scale is not necessarily local: connected to other scales (impacts down-streams). No clear lines between different forms of knowledge in understanding the river (e.g. river keepers interact with environmentalists, authorities etc.).

- Catharina Landstrom: how experts know and understand drought.

- Creation of a new scale via mathematical models; accessing it with instruments, the scientific tool-box. The scales are created in the practices: they are socially constructed.

- Some of the key questions looked at in these studies are the following:

Christopher Duffy, Penn State University, USA: On the concentration-discharge signature of drought in rivers: a dynamical systems view

How do we calculate hydrologic time?

- Kinematic age of water along a flow path

- Analogy with population

- As long as there is water going into the system, there will be finite age in the system. If the water is turned off, the concentration stays the same and the age goes up. Droughts are like clocks: they slow down water cycle, so tracer ages in proportion with time.

- A truly dynamic system: particles in the system a function of flow and the concentration and vary tremendously;

- Study at Pennsylvania catchment: map age of water over water-shed (=mapping of older and younger mapping with implications for the droughts). Observed trend slowing down the hydrological cycle over 30 years, and hoping to determine what causes the trend: the climate (drying) or the ecology (e.g. tree growth leading to water use: a biological drought).

- Implications: the hydrological cycle is decelerating due to biology or climate change

Greg Garfin, University of Arizona, USA: Coping with Drought in the American Southwest

- Drivers of South-west

- Diverse topology, climate and hydrology

- La Nina/El Nino weather

- PDO

- One consequence of drought is the increase in conifer mortality (as a result of water stress, increase life span of pests, forest fires and erosion). Fires are extremely costly!

- Water Management causes of water scarcity in the Colorado river basin: over-allocation in the late 1900 of the Colorado river (the C river was allocated during a wet period – not reflective of average river hydrology)

- Other causes of the California drought:

- Population increase over the last century;

- Expansion of agriculture (thus increase in agricultural water demand); to make up for surface water shortages, farmers have been using groundwater leading to over-abstraction and aquifer stress;

- Farmers shifting from vegetable crop to nut crops (high value crops, very water demanding);

- Rise in per capita demand;

- Climate change?

- Planning:

- California 1st drought plan, 2010. Attempt at integrating water resources planning and drought planning; however, failed to consider droughts would occur faster. No requirements for agricultural contingency plans.

- Arizona

- Groundwater management act 1980 (to be put into practice in 2025)

- State law that fail to acknowledge connection between ground wand surface water

- Good thing: very active state drought monitoring committee; water providers and agencies are required to provide contingency plans;

- Little assessment of past drought; of the water-energy-food nexus;

- Conclusion: we can learn from the successes and the failures; need to be more creative and imaginative (use wider array of options: conservation, developing new infrastructure, technologies).

Peter Wallbrink, CSIRO, Australia: Using water management models to support risk based decision making for climate and agriculture in South Asia: The Indus basin

- Working in 3 basins: 1. 2. Brahmani Baitarni (working with 3 states to help them understand the basin planning); 3. Indus Basin (Take more ownership of their part of the Indus water treaty;

- Indus Basin:

- Characterized by uncertain hydrology; uncontrolled use of groundwater; relationship between GW and surface water not well understood; increase in demand;

- Aim is to develop a model that allows water managers across boundaries to take care of the day to day management of the river; manage uncertainty; plan potential future uses under climate change scenarios;

- Capacity Building

- Brahmani Baitarni Basina

- Aim: Basin planning to help them take ownership of their future; Build consensus with the states around using the model for water management planning;

- Modelling flows under different scenarios

- Conclusions:

- Engage with stakeholders at many levels;

- Need to share knowledge;

- Underpins process for risk based food and drought management;

Lee Godden, Melbourne University, Australia: Drought and water scarcity issues in Australia

- Drought is a relative concept. We have a social system that responds to a physical system. We cannot understand drought in a unique straight-forward way. In this context, the following questions become relevant and important to consider:

- If risk is relative and water scarcity influenced by socio-cultural factors, what does it mean to be responding to the impacts and uncertainties?

- What exactly are we responding to? (e.g. by focusing on droughts we forget the cyclical nature of droughts: the combination of droughts + floods)

- How we frame the problem is key to the decision making process.

- Australia’s Adaptation to droughts demonstrates how complexity was governed across scales

- Australia Water Law

- Australia inherited UK riparian doctrine in water law à process of adjustment… does not fit with Australian geography

- Australia as a country of water dreamers and drought deniers

- Crown vested water resources early 20th century

- Crown government has control;

- Reforms from 1980s

- clear that there was extensive over-allocation

- early drivers for water law reform was water quality (salinization)

- Water Law and Policy Reform à how to deal with severely over-allocated basins

- First stage of reform; separate land and water entitlements (can be shared, bought, leased, mortgaged); MDB cap; start to think about environmental requirements

- 2004: national water initiative

- series of principles; improved security of water allocation

- encourage water conservation

- 2007 – water act

- basin plan – sustainable diversion limit (limit has been contested)

- climate change risk formula (largely a financial risk formula – who bares the cost of change?)

- separation land/water; unbundling of entitlements in rural areas

- Conclusions:

- A LOT of public money invested

- SDL very contested

- But considerable economic benefits from NWI reforms (70% reduction of water diversion in drought)

- Putting in place the legal framework for water trading

- New entity: commonwealth environmental water holder (largest holder of water entitlements)

- More recently other innovative options have come to the fore to rethink the water supply (e.g. desalination: Making Melbourne ‘Drought Proof’; urban design; rain-water harvesting).

- Innovation is key here. We must start to re-think the ‘hydro-social contract’, rethink path dependency. Rethinking the cities as a catchment (Urban Design), using the cyclical natural of drought and flood.

- Conclusion: Initial problem framing is critical (What is drought? Could we start planning for them as the norm?); Australia had a hard look at its own legal structures and changed them. Truly innovative and creative changes then can arise.

Drought Risk in the context of change

Magdalen College, Oxford. 22 September 2014

This symposium took an interdisciplinary approach, looking at the climatic and socio-economic factors that are contributing to the changing risk of drought. Below is a summary of the event, with links to some of the presentations (in pdf format) where available.

Professor Jim Hall (University of Oxford) opened the Symposium

Jim gave a summary of the current UK research into drought. Following the 2011-2012 drought a joint programme of multidisciplinary research has been initiated by the UK physical and social research funding councils, called the ‘Droughts and Water Scarcity Programme’. The programme goals are to characterise the drivers and nature of droughts and water scarcity; examine the multiple and inter-linked impacts of UK droughts and water scarcity on the environment, agriculture, infrastructure, society and culture and the trade-offs between them; and develop methods to support decision making for drought and water scarcity planning and management.

This symposium has been arranged through the MaRIUS project (2014-2017) which is the biggest project within the programme, and of which Professor Hall is the Principal Investigator. The MaRIUS project – Managing the Risks, Impacts and Uncertainties of droughts and water Scarcity – assembles a team of physical and social science researchers from the universities of Oxford, Bristol, Cranfield, the Meteorological Office and the Centre for Hydrology and Ecology. They are assisted by a stakeholder advisory group and a team of international experts to help steer and guide the project.

The MaRIUS project vision is to help us move forward towards a situation when the future management of droughts and water scarcity will be more explicitly risk based, and will be founded on evidence of the full range of drought impacts on people and the environment, and a systemic understanding of interactions and uncertainties. To help achieve deliver this vision, the research focuses on three areas: firstly the characterisation and quantification of the roles of multiple drivers, their impacts, and cumulative effects during historic periods of drought and water scarcity. Secondly, it generates and uses forecasts of droughts and water scarcity in hydrological and water resources models. Thirdly, the project will assess the impacts of droughts and water scarcity on people and the environment, and will develop methods to support decision-making to reduce risk.

Prof Christopher Duffy (Penn State University, United States) detailed his current research in exploring “a catchment-based, distributed approach to the impact of drought on wetland ecosystems”.

Chris outlined the concept of ‘Essential Terrestrial Variable’ (ETVs) in understanding drought and explored issues of temporal and spatial scale or resolution of the use of ETVs in catchment research. ETVs include atmospheric variables; terrain, soil and hydrological information; and water and land use amongst other factors. Conceptual models are very useful in establishing the principles of physical processes and help to bridge the difference in outputs between field observations and model outputs, and also the outputs of models with different data needs. Chris outlined his team’s ongoing research and model development and testing in the instrumented Shale Hills/Susquehanna wetland catchments. The research focused on an assessment of wetland vulnerability to climate change, and looked at 7 catchments, two 20 year climate scenarios, and 4 different ecoregions within the catchments. Early results showed that there is no consistent trend with regard to the desiccation of different ecotypes although it seems that upland catchments are the most impacted landscape based on depth to groundwater.

Chris also highlighted the need for consistent and accessible spatial datasets to permit research at the catchment scale. In this US, this is problematic as there are over 103,000 recognised catchments and no federal organisation collecting data across the country. In their work, Chris’ research team brought together over 300TB of data from a very large number of sources.

Dr Henny van Lanen (Wageningen University, the Netherlands) spoke on ‘Past and future drought in Europe’.

Click here to download the slides from his presentation

Henny explored the urgent questions about drought in Europe: what are the observed trends; and what will the future bring? Our ability to identify trends is constrained by available data, different definition of what is a drought, different ways to quantify or identify a drought, and the inability of models to include all the factors that influence a drought. Different model types also show different results, with large scale hydrological models show a greater spatial extent of drought than global circulation models. These factors lead to uncertainty and a limitation on the confidence that we can apply to the identification of drought episodes. For example, the unequal spatial distribution of monitoring locations (e.g. river flow) hinders the examination of the spatial extend of drought, and calibration and validation of models. The time period over which drought is assessed can also affect the identification of whether or not a drought occurs. For example, an assessment of river flow using annual mean flow statistics shows fewer droughts compared to the use of an annual 7 day minim flow for example. Further, Henny showed archival data from the Jucar Basin in Spain to highlight that drought trends can be considered on intercentural as well as interdecadal intervals, showing that drought is a natural phenomenon. It is important therefore to take a specific drought definition and consider the effect on humans, using time series of hydrometerological variables. It is currently thought, with medium confidence, that droughts will intensify in the 21st Century, but this will not be homogenous: rather it will happen in some areas and some seasons in southern and central Europe, centre North America, Central America and Mexico, Northeast Brazil and southern Africa. Elsewhere there is low confidence attributed to drought change predictions, due to model inconsistencies.

Henny also highlighted that when considering future droughts, the default is consider an abrupt change (i.e. without any adaptation to the change in hydrological between now and the future) which will incur the greatest impact. However, humans will adapt and make adaptations to the changing regime and this will influence the characteristic, extent and severity of the impact of future droughts.

Professor Lucia De Stefano (Complutense University of Madrid, Spain) spoke on the subject of ‘Understanding vulnerability and response to drought: from a local to a pan-European scale’.

Click here to download her slides

Lucia presented research on the vulnerability to drought undertaken by herself and her team on exploring the experience of working on the same issue (drought) with different approaches, perspectives and scales, using a pan-European scale and a country specific (Spain) scale. The research found that different scales created different perspectives, and that there are inconsistencies in drought perceptions across scales. For example in Spain, at a national level, drought is not considered normal; however it is considered normal at the river basin management level. On a finer scale still, that of the irrigation district, the boundary between water scarcity and drought is sometimes blurred. Differences in response and vulnerability evolve over time leading to a difference in the adoption of collective strategies.

The research concluded that comparison is useful but that assessing measures and vulnerability across scales is challenging. Discourse analyses is useful to understand the underlying logic that affects drought actions at the different scales, and stakeholders input is essential to really understand vulnerability and response to drought. Drought management can be enhanced by the improvement in communication consistency and across scales so that efforts made at a certain level will also positively impact other levels. This will hopefully address inconsistencies between policy objectives and implemented measures, and enhance data collection and data access to generate evidence based decisions.

Dr Narendra Kumar Tuteja (Australian Bureau of Meteorology) gave an Australia perspective on ‘Water availability forecasts for operational planning and management’.

Australia has faced about 8 major drought events in the last 100 to 115 years: the Millennium drought (1997-2009) has had the most impact and has radically shaped the water reform agenda in Australia. Narendra talked about the an extensive user needs analysis in Australia which highlighted the desire and need for water availability / stream flow forecasts at a range of time scales, and the challenges in achieving these. He emphasised the need for continued and extensive liaison and consultation with stakeholders and users: a full two way exchange in order to fully understand and deliver useful research, data or tools. Engaging with stakeholders meaningfully, establishing R&D alliances and transitioning research to operations is not trivial and should not be underestimated; not least the communication of forecast uncertainty and performance. Influencing decision making by water resource managers requires ongoing engagement throughout all stages of planning, development and delivery of water and that making the right technology choices is critical for development and delivery of operational forecasting services.

Professor Casey Brown (University of Massachusetts, United States) ‘Climate stress testing to reveal vulnerability to climate change’

Click here to download his slidesCasey was able to successfully deliver his presentation from a French airport through the technology of Skype and Wi-Fi! Despite his being remote from the audience (and not being able to see and only just hear the audience), Casey was able to connect directly to the listeners and give an engaging talk.

Casey outlined the problems facing the water planner: as the statistics used to design and operate the water supply system may not be indicative of future climate, and future drought risks may be greater than historical, or not, this can lead to substantial possible regrets for any decision taken. He defined the difference between a traditional top-down climate projection led analysis, compared to a decision scaling approach, and advocated the latter. Given model uncertainty and natural climate variability, Casey argued that the best approach is to focus on understanding the project and its vulnerabilities to climate change, to reveal the key climate variables to which the system is sensitive, and the magnitude of climate changes that cause unacceptable outcomes. On this understanding a water planner can incorporate the desired or acceptable level of resilience into the project.

Professor Donald Wilhite (University of Nebraska, United States) closed the symposium by giving the keynote address on the subject of ‘Managing drought risk in a changing climate: the role of national drought policy’.

Click here to download his slides

Donald is a founding director of the National Drought Mitigation Centre and chair of the Management and Advisory Committees of the newly formed Integrated Drought Management Program (IDMP) launched by the World Meteorological Organization and the Global Water Partnership. Donald’s presentation made the audience aware of the need to break the hydro-illogical cycle of contemporary crisis management to one that is based on risk management, underscoring the need for change with the phrase: “If you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you’ve always got!”

Although drought is a normal part of climate variability, it is commonly met with shock and alarm when it happens, from an unprepared government and vulnerable society. Instead droughts can be viewed as a window of opportunity to change from post-impact interventions (i.e. crisis management) to pre-impact and mitigation programs coupled with risk-based drought policies and preparedness plans, organizational frameworks and operational arrangements. The cost of action against drought is insignificant when compared to the cost of inaction. Donald outlined the progress made towards the implementation of Drought Plans across the world through the Integrated Drought Management Programme which has the objective of supporting stakeholders at all levels by providing policy and management guidance and by sharing scientific information, knowledge and best practices for Integrated Drought Management. The development and a success of a Drought Policy depends on a range of factors, not least the political will and leadership in the particular country, but also supported engagement and coordination between the government, private sector and stakeholders. The drought policy should be implemented via a Drought Preparedness Plan that should outline the monitoring prediction and information delivery systems; risk and impact assessment and the required mitigation and response measures.

Donald concluded by stating now is the time for a paradigm shift from a post-drought crisis response, to a prepared drought-risk management approach.