Key science findings

- Droughts can alter the processes that govern ecosystems, causing changes to physical character, species occurrences and numbers, their interactions and benefits they provide to people.

- River flows are reduced by droughts, making conditions unsuitable for many species.

- River habitats can be fragmented preventing normal species movements required for feeding, predator avoidance and reproduction .

- River ecosystems can recover from drought; the time taken depends on the species (algae 1 month, higher plants 1 – 3 years, macro-invertebrates 1 year, fish 1-3 years). Much depends on the severity and duration of the drought.

- Under future climates, droughts may occur more frequently reducing the time available for full ecosystem recovery.

Introduction

Droughts have the potential to affect a wide array of habitats and species in river ecosystems according to their magnitude, timing, frequency and duration. The water requirement of plants and animals varies according to the species, and therefore, so do their tolerance and response to drought. This is important because it is species assemblages that support the healthy functioning of ecosystems, for example through the structure of food webs.

In rivers, droughts reduce the amount of wetted habitat, while they increase water temperatures and decrease water quality. The resulting degradation of the habitat leads to reduced abundance, species diversity and ecological functioning in aquatic plants and animals.

Given time, organisms and habitats may recover fully, because they have evolved strategies to be resilient to drought. However if droughts are severe, prolonged, or so frequent that recovery time is insufficient, species can be locally lost and habitats altered, compromising ecosystem functioning.

Research methods

In addition to a detailed review of evidence of how droughts affect river ecosystems over different time periods, we have taken three approaches to analysing the ecological response to drought in UK rivers:

- hydrological alteration (general and event-based); analysis of the indicators of hydrological alteration defining the hydrological aspects of drought but using metrics that are ecologically relevant

- eco-hydrological modelling (response of biological index to flow change)

- eco-hydraulics (physical habitat and connectivity); analysis of physical habitat structure, focusing on fragmentation during droughts

Result 1: Hydrological alteration

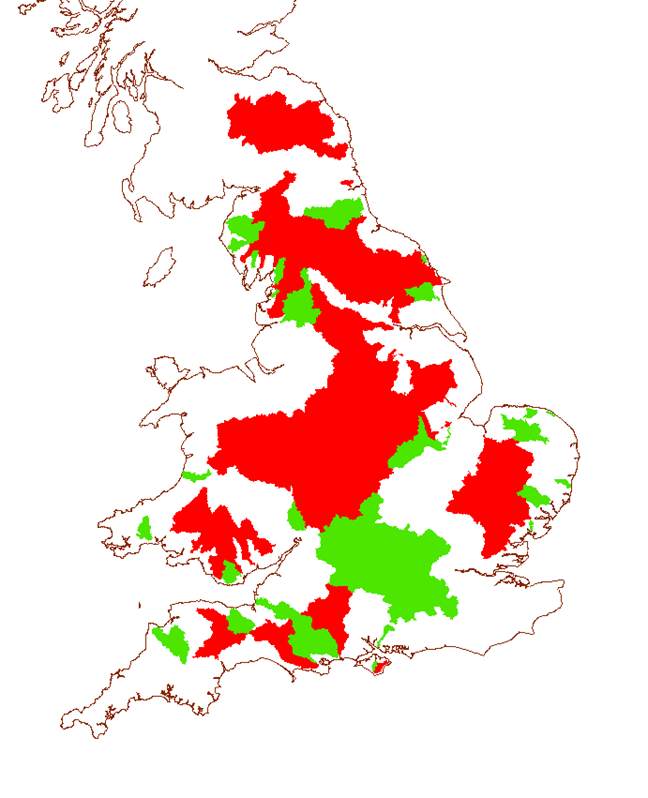

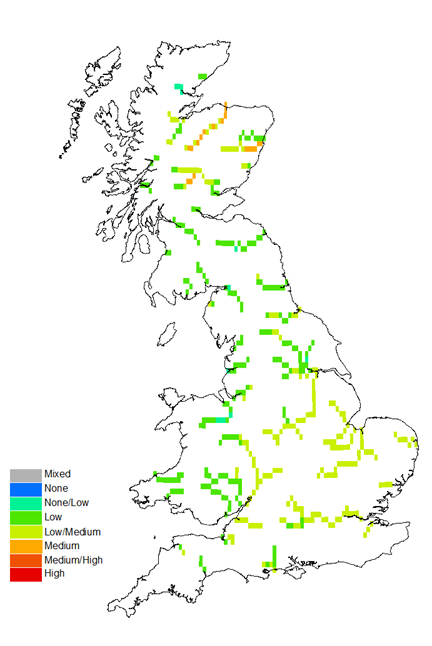

The eco-hydrological literature supports the concept that all aspects of the flow regime matter to riverine ecosystems. Any major departure from usual conditions is therefore associated with the risk of an impact to the system. This forms the basis for the two hydrological alteration approaches used in his project: (1) Ecological Risk due to Flow Alteration (ERFA) method, developed by CEH, and adapted for MaRIUS (2) Drought-specific G2G metrics. ERFA used 16 hydrological indicators based on monthly flow data to characterise all aspects of the flow regime. Drought-specific G2G metrics include: month of longest flow deficit of the year ending (if any); month of longest flow deficit of the year starting; number of flow deficits per year (ie frequency of droughts); highest change in flow going into a deficit; highest change in flow recovering from a deficit; length of drought.

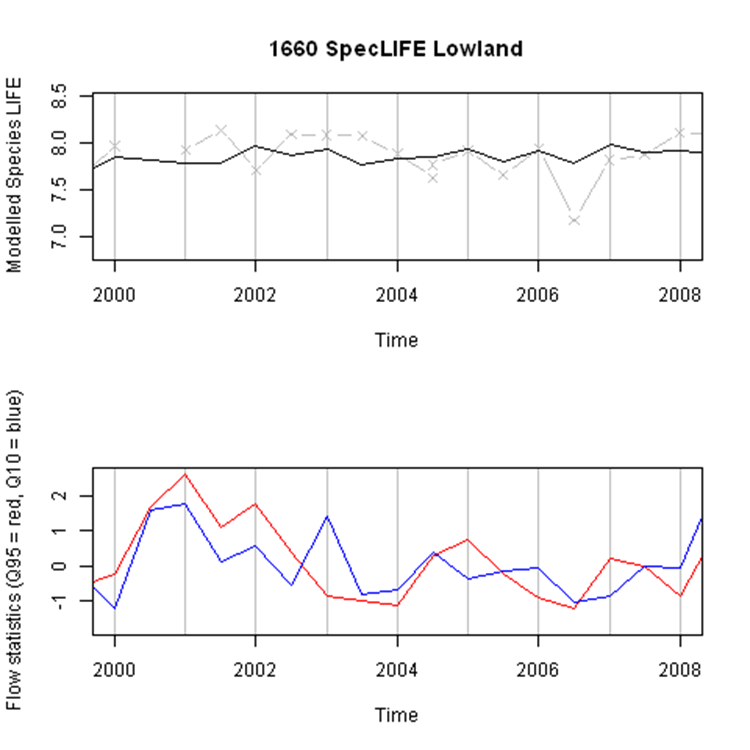

Result 2: Eco-hydrological modelling

We investigate observed biological data, in order to model the biological response to flow change, then to generate simulated responses to all flows available to the project (baseline and drought event sets). In practice, we use a bespoke version of a CEH model focused on biological indices for river invertebrates, which assesses the response of the indices to one or several flow metrics. Once fitted with observed data, the model can produce simulation using the G2G flows for the drought event set, thus generating matching series of biological index responses.

Result 3: Eco-hydraulics

River organisms not only react indirectly to discharge, but also are directly sensitive to river hydraulics (the “missing link between hydrology and [river] ecology”) in two main ways:

(1) Loss of physical habitat diversity, in terms of depth, velocity, etc., created by the interaction between discharge and the channel morphology (2) loss of longitudinal connectivity between sections of the river network when channels dry out (ie less opportunity to explore food sources, or to find most suitable conditions); particularly relevant to more mobile organisms like fish

Hydraulic geometry models have been fitted at ~200 sites in England and Wales. Modelled flow data (G2G) are used as inputs to generate series of mean velocity, mean depth, and wetted width at these sites. A site-by-site analysis allows to gauge how much physical habitat may be lost during droughts. Modelled depths are then used to assess loss of connectivity within major catchments.